Australia’s geoscience paradox threatens its prosperity and sustainability

Unprecedented climatic, environmental, energy, and resource crises threaten our world due to a growing, unsustainable human footprint on our planet. But while Australia awaits national strategies to address climate change amidst the COVID-induced recession, deep staffing cuts and closures of tertiary geoscience programmes across the country compromise our collective ability to respond to these challenges.

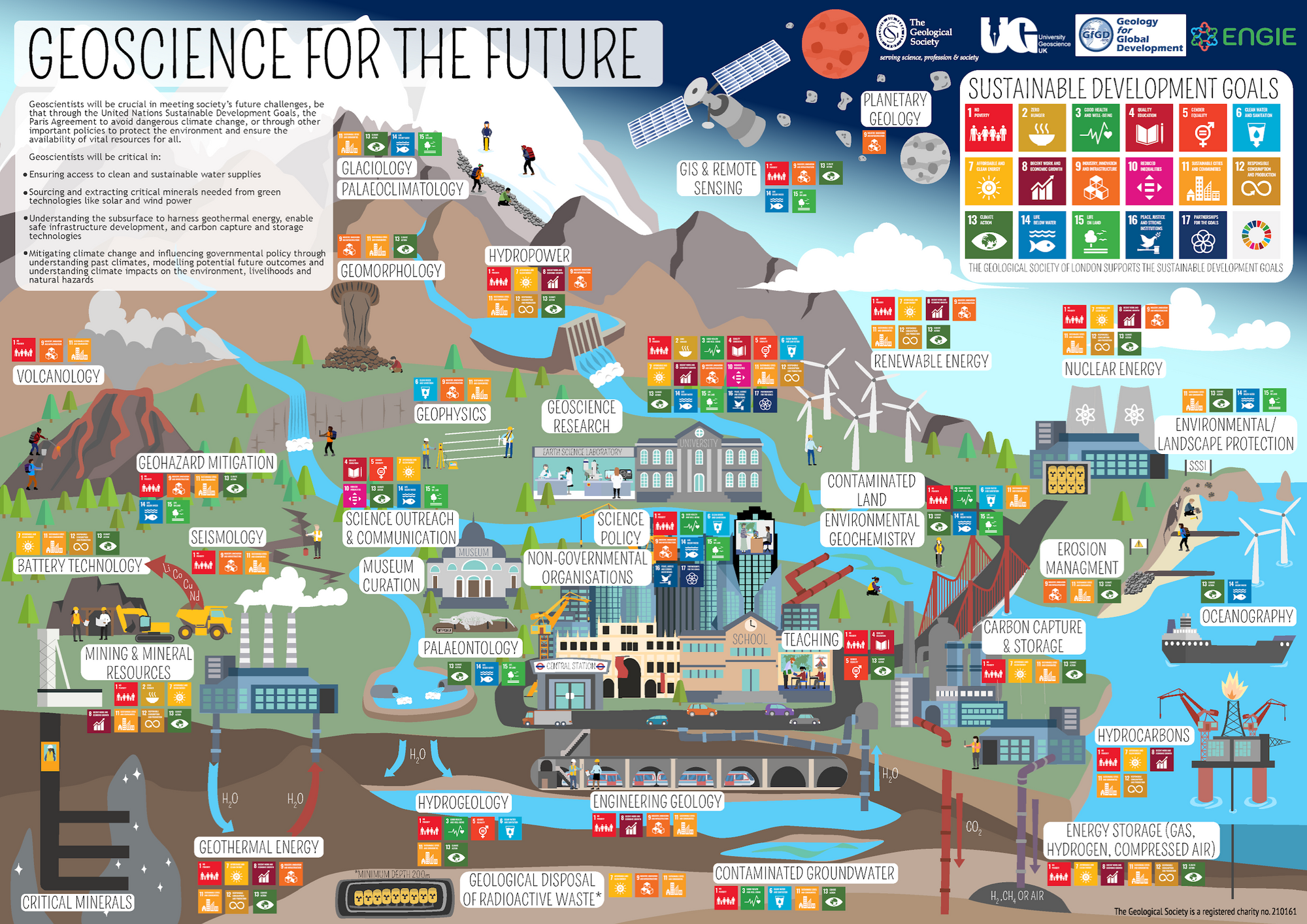

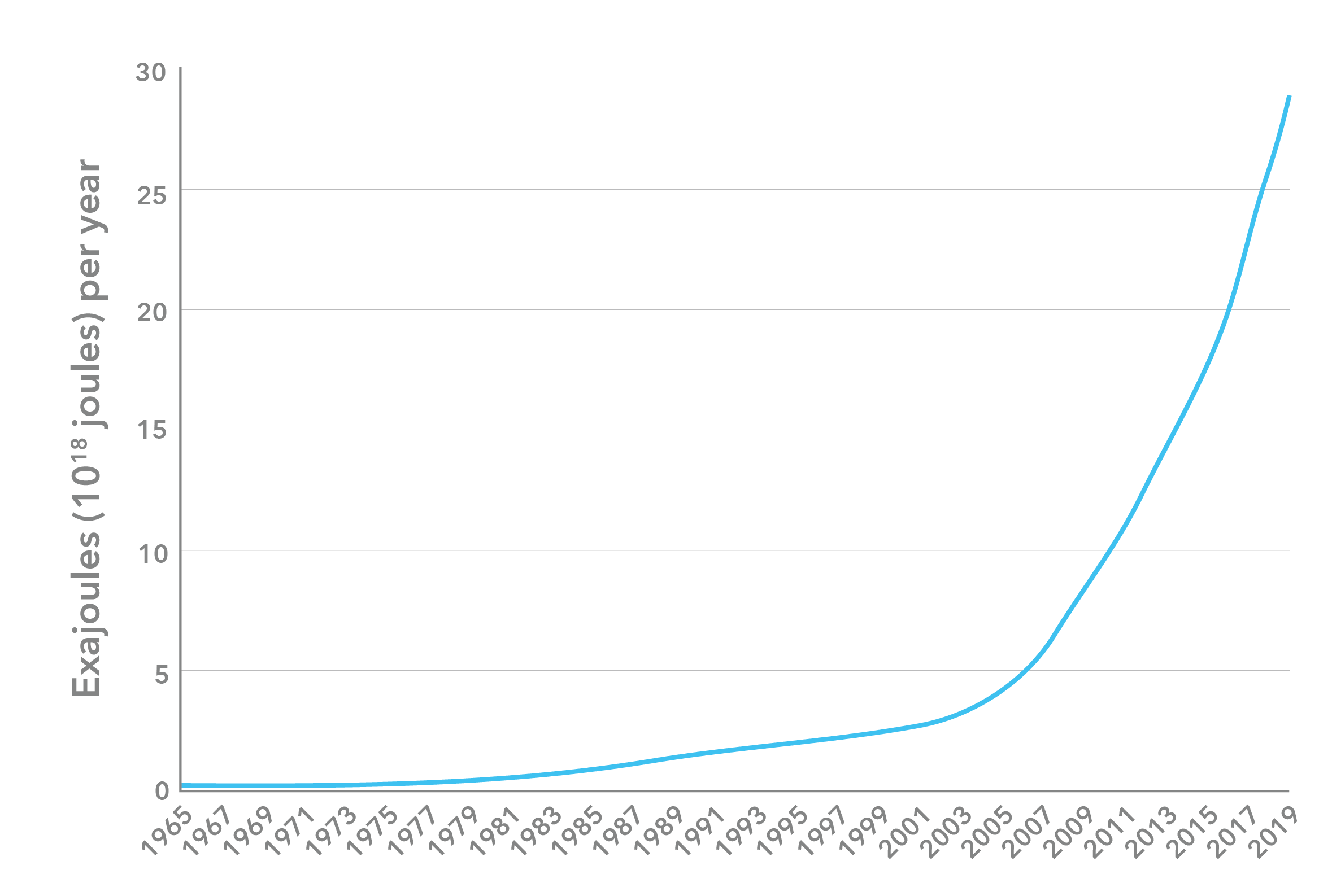

Geoscience is the interface between humanity and Earth, studying the processes that shape its environment, the natural resources it provides, and the relationship between water and ecosystems. As such, it is key to ensuring a sustainable future for Australia’s infrastructure, environmental and energy industries, essential to tackling climate change and powering our recovery from the tumultuous economics of the COVID-19 era. On a global scale, the United Nations and World Bank have championed geoscience as essential to reaching its Sustainable Global Development Goals, a critical component of disaster risk reduction and vital to achieving the Paris Climate Agreement, as the need to deploy clean energy technologies will result in a 500% increase in critical minerals demand.

But paradoxically in Australia, geoscience is currently under threat of domestic extinction.

A recent string of closures, cutbacks and mergers of geoscience departments across the country in response to financial pressures and low student numbers raise palpable fears that Australia will rapidly become a nation unable to tackle the imminent challenges it faces. Diminishing the community of experts in tertiary institutions reduces our domestic capacity to educate future generations of geoscientists demanded of our major industries.

To preserve Australian geoscience capability, strategies must be developed to increase appeal to students, prompt greater university endorsement, and obtain additional government and industry support based on strategic national benefit.

We offer exploratory avenues to help save Australian geoscience.

A new identity for geoscience

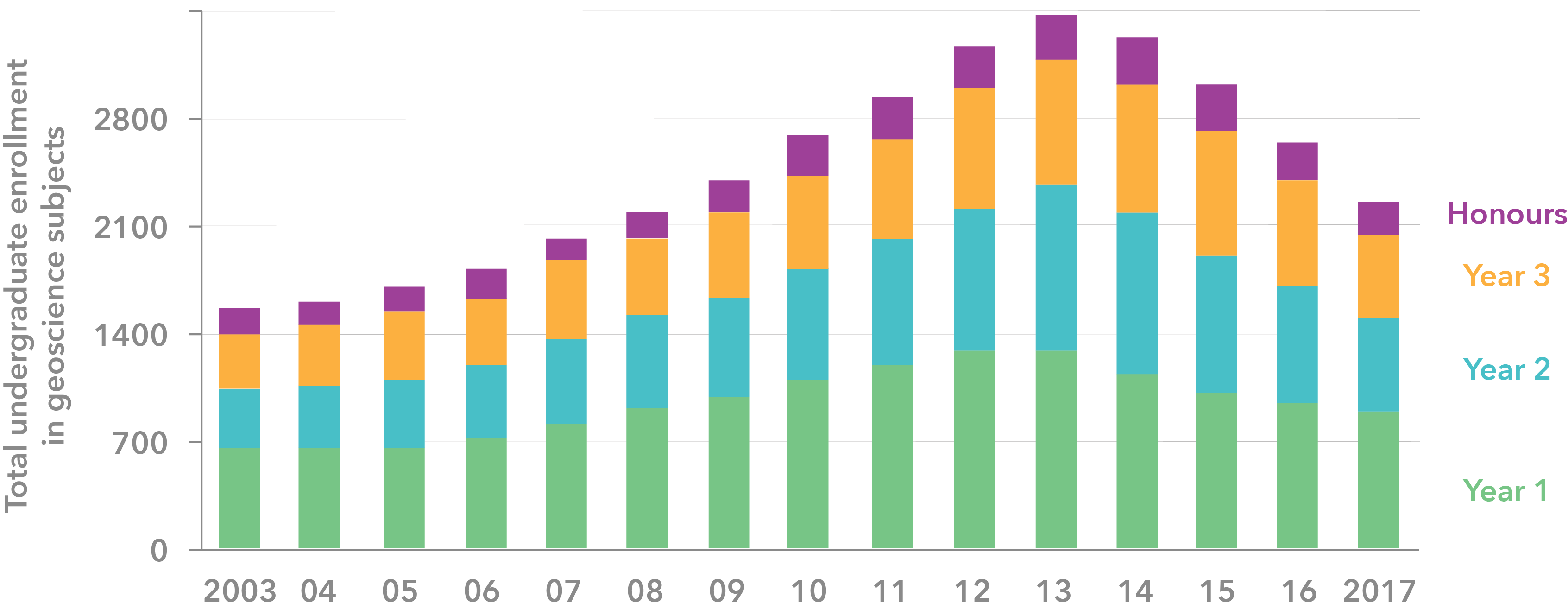

Tertiary student enrolments in geoscience majors have dwindled at many institutions across Australia, despite increasing industry demand for graduates and abundant evidence for rapid graduate employment across diverse sectors outside of the mining industry. In large part this stems from an unfortunate perception of geoscience as feeder to polluting industry plagued by instances of ethically apathetic practice, misaligned with the prevailing values of contemporary students.

Thus, an all-hands-on-deck approach is needed to recast the geoscience narrative as a mechanism for meeting society’s challenges, better reflecting the true breadth of its disciplinary applications.

Geoscience informs disaster preparedness, response, recovery, and resilience strategies at home and abroad, across the full spectra of natural and anthropogenic hazards. It provides a vehicle for purposeful domestic and international aid in the face of crisis and contributes valued evidence to deliberations on Australia’s water security and marine jurisdictions. And it enriches our knowledge of Australia’s Indigenous peoples through the study of ancient art, landscapes, and materials and thus has the potential to supplement reconciliatory activities.

So, to what extent should geoscience curricula be overhauled to ensure the vehicle for content delivery is aligned with contemporary student values? For example, could inter-disciplinary lessons on environmental and mining ethics form a more substantive component in subjects on Earth Resources? And could Indigenous cultures, engagement protocols, and Ways of Knowing be better integrated into geoscience curricula in such a way as to re-position geoscience as a vehicle for increasing cultural understanding and landscape value?

A national dialogue is needed to develop a revived and unified geoscience education narrative that captures the imagination of Australia’s youth.

Socialising the cost of curricula diversity in Australian universities

As a flow-on consequence of "the federal government’s refusal to financially back the [university] sector during the pandemic-induced recession", academic departments are being forced into cutting staff and costs. Thus, universities across the country are consolidating their educational offerings to those which attract the greatest number of secondary school graduates and appeal to higher fee-paying international students.

This is particularly true of geoscience programmes, whose viability in universities has been questioned and substantive reductions in staffing and curriculum offerings, including termination of geoscience programs and departmental mergers, have been enacted at several institutions across Australia.

However, a change in perception for young Australians and the envisioned uptake in undergraduate geoscience enrolments will not occur overnight. In the interim, universities may consider their responsibilities of sustaining diverse curricula to ensure provision of opportunities for students to meet future societal demands, accordant with the tenet of patrons of collective fundamental knowledge which they claim.

National strategy for geoscience teaching and capacity

Unfortunately, we cannot expect universities, as businesses, to make decisions solely based on national benefit.

Instead, national policies are required to temper the fiscal decisions of institutions and ensure Australia has a future geoscience workforce, enabling it to build sovereign capability, independently address climate change and economically benefit from the global renewable energy revolution.

Namely, a national strategy for geoscience teaching, capacity and research is needed, similar to the successful Australian Mathematical Sciences Institute and Minerals Tertiary Education Council. With new investment aligned to this strategy, teaching hubs across several universities could be identified and developed in areas of strength and strategic importance. This could include hubs specialising in renewable energy and critical mineral exploration, applied geophysics, water resource management, carbon sequestration and geohazard mitigation.

A strategic national geoscience program would not only protect geoscience education from further financial instability in a weakened university sector but could propel Australia’s recovery out of the post-COVID recession as global leaders in the new green economy.

Saving Australian geoscience

Ensuring a sustainable and prosperous future for Australia requires saving and empowering its geoscience expert community. To do this, national strategies involving geoscience, university, industry, and government stakeholders are needed that include:

- A unified recasting of the geoscience narrative in line with contemporary student values to increase undergraduate enrolment

- Long term endorsement by universities, in the name of fulfilling future needs and providing diverse curricula

- A nationally coordinated strategy for teaching and research to ensure future geoscience capability.

Edited by Louis Moresi