The Dynamics of Continental Accretion

In a recent paper [1], we used Underworld models to examine subduction congestion associated with the ingestion of a continental ribbon. The SE Australian geological record turned out to be a wonderful place to study this process. Here is a short summary of the work for a relatively non-technical audience that we put together and some additional figures which I prepared.

[1] Moresi, L.N., Betts, P.G., Miller, M.S., and Cayley, R.A., 2014, The Dynamics of Continental Accretion: Nature, doi:10.1038/nature13033. Also see supplementary information and animations

Summary

The Earth’s continents drift at a speed of just a few centimetres per year driven by the sinking of the cold tectonic plates at subduction zones. As they drift, continents collide to form great mountain belts and, in the process, incorporate an assortment of geological debris. This activity has shaped the geological record for billions of years and geologist are accustomed to finding “exotic” material mashed up in ancient mountain belts.

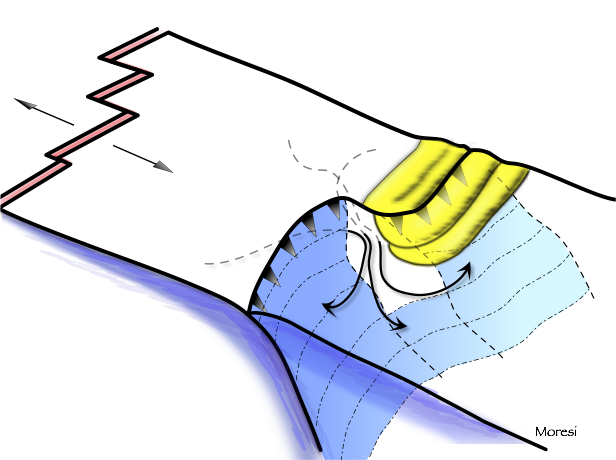

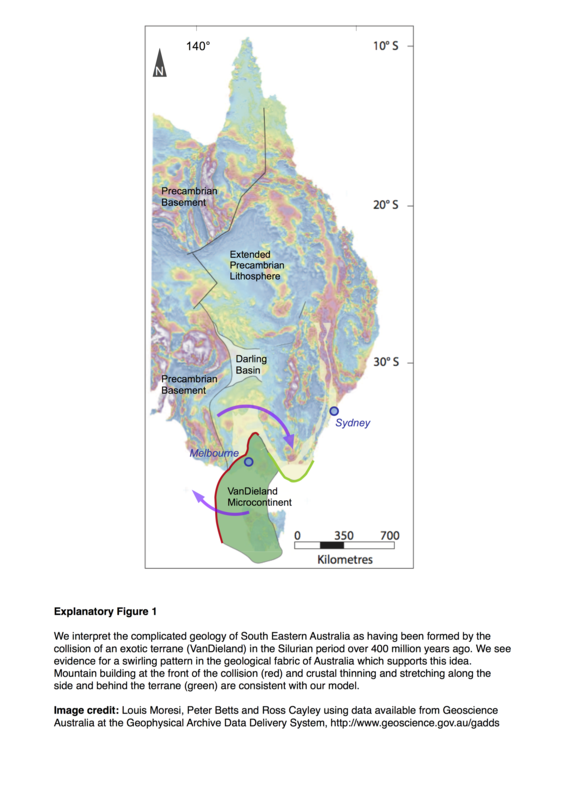

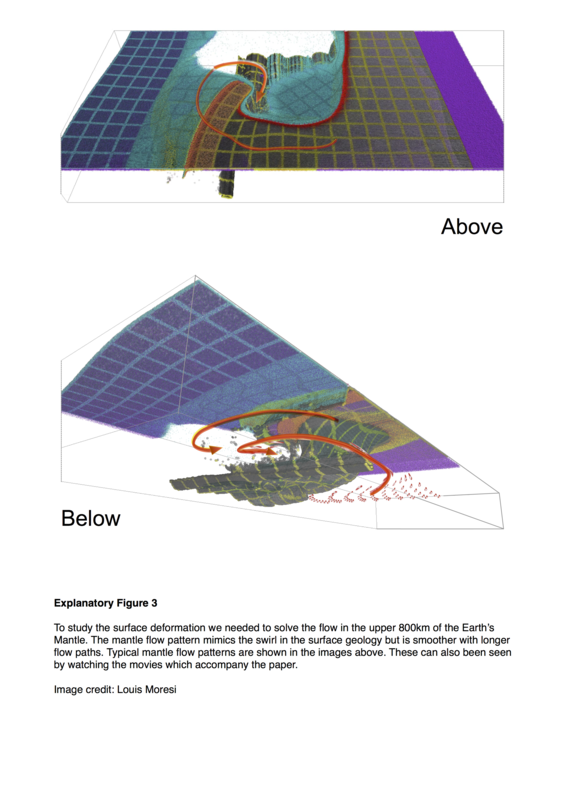

The paper by Louis Moresi, Peter Betts, Meghan Miller and Ross Cayley shows how continental collisions work — how subduction zones stutter and recover when they are hit by a drifting continental fragment, and how evidence of such collisions may remain preserved largely intact in the Earth’s crust for hundreds of millions of years. The research shows how the subduction zone and the exotic continent dance around each other during the collision leaving a distinctive pattern in the rock record. The researchers predict that regions where collisions occur, crumpling up the crust into mountain belts, are flanked by low-lying zones of stretching and extension, characterised by intense localised heating, volcanic activity and fresh sediments that, till now, appeared enigmatic. Rocks caught up in the collision are swept around in a huge arcing path, stretched, rotated and dragged hundreds of kilometres from their original location as they chase a curved subduction zone trench retreating oceanward — a process called ‘subduction roll-back’.

One place in the world where evidence of this unusual pattern had already been observed happens to be on our own doorstep. The geology of Victoria, Tasmania, and New South Wales shows an embedded block of older continental crust which collided with SE Australia between 450 and 380 million years ago. The collision started a cascade of geological processes that resulted in a swirling pattern preserved in the surrounding rocks, exactly as predicted by the computer model.

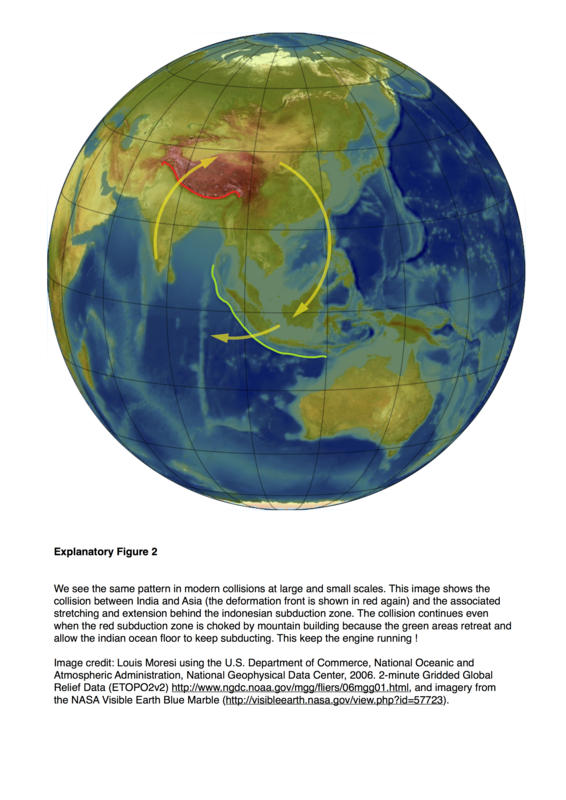

The results of the research may explain complex geological relationships in the modern Earth, including the contorted geological patterns where the northern margin of Australian tectonic plate is colliding with smaller micro-plates of SE Asia. Geometries predicted by the models are also seen in the tectonically active Mediterranean region in Europe, and contorted Mountain belts preserved throughout western North America.

The results will help geologists interpret ancient Mountain belts; this includes other parts of Eastern Australia as well as Central Asia, which are the sites of some of the largest accumulation of the Earths continents in the last 500 million years of Earth’s history. The results may prove most useful as a template to interpret regions where preservation of evidence for past collisions is incomplete — a common, and often frustrating, challenge for geologists working in fragmented ancient terranes. Geometries predicted by the models will radically redirect the focus of exploration for buried mineral systems already known to be intimately linked to the plate-tectonic process — they will occur in places not previously suspected.

The results will also likely provoke significant re-interpretation of some ancient deeply-buried geology, for example beneath the Antarctic icecap, where the accumulated geological history is tantalisingly revealed only as patterns in regional-scale geophysical datasets.

Glossary

Plate tectonics — the process by which the Earth turns itself inside out, creating new sea-floor at the mid-ocean ridge and swallowing it again at subduction zones. This process turns the Earth’s internal heat into surface motion of a few centimetres per year and provides the energy for geological change.

Continental Drift — the continents are shuffled, deformed, and dragged around by plate tectonics but are not recycled into the Earth by subduction zones because they are made of generally lighter rocks. The geological record clearly records the fact that for billions of years continents have migrated continuously around the Earth’s surface: colliding with each other, rifting apart, and drifting to different climatic zones. Modern satellite-based Global Positioning System measurements confirm beyond all doubt that this process continues today.

Mountain Belts — Mountains usually occur in long, relatively narrow chains across the Earth’s surface. This reflects the fact that subduction tends to occur along a wide region of a plate boundary and that subduction is the driving force for mountain building. So much so, that breaks in mountain belts invite special explanations such as collision of exotic crust. Actual mountains erode very quickly in geological time, so ancient mountain belts are recognised by geology characteristic of deeply eroded mountain roots, compared directly to modern examples.

Subduction Zone — A convergent boundary between two of the Earth’s tectonic plates, whereby a denser oceanic plate sinks into the Earth’s mantle, moving beneath an overriding plate of either continental or oceanic character. Active subduction zones are sites of volcanism, earthquakes and mountain building. Fossil subduction zones can be challenging to recognise in the rock record.

Additional Figures

Originally published at https://www.underworldcode.org on April 1, 2014.